Government Shutdown of an Estuaryby Dani Madrone

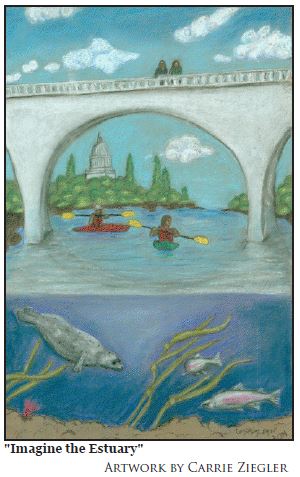

Under the government shutdown, all activities and services were suspended until further notice. However, while the gates to the delta were closed, the estuary continued its many beneficial services that contribute to food systems, public health, flood protection, aesthetics and an overall sense of well-being that comes with people's interaction with the natural environment. An estuary is where the river meets the sea. Estuaries offer fundamental and irreplaceable services, including filtration of pollutants from the water, natural and bio-diverse habitat, a buffer to stabilize shorelines, and protection of inland areas during storms and floods. They offer protective nurseries and brackish water for salmon to transition between fresh and salt aquatic environments. They create and contain habitat for many marine animals, including birds, seals and shellfish. They offer a place of beauty, refuge, connection and recreation. They support water, vegetation, wildlife and people. Even during the government shutdown, the Nisqually estuary thrived. There is comfort in knowing we can fall back on natural systems when our human-made systems are failing us. But can our government shutdown ecosystem services? What happens when our human-made systems interfere with natural systems? The loss of the Deschutes River Estuary in South Puget Sound offers insight to these questions. It is a local estuary that has suffered through a shutdown of its critical ecosystem services for over 60 years. In 1951, the state of Washington dammed the Deschutes River at its mouth to build a road to connect downtown to West Olympia. Ever since, Capitol Lake has been filling with river sediment at a rate of 35,000 cubic yards per year. Normally, the river would carry the sediment through the estuary and to the Sound, where it would distribute to build beaches and critical habitat. Because of the size and shape of Capitol Lake, it has poor circulation and the water is stagnant. Algae and invasive plants and snails grow in the warm, shallow waters. When they decompose they pull oxygen out of the water. This dissolved oxygen is necessary for fish to breathe, and Capitol Lake has dangerously low levels. In fact, the dam is the main cause of low dissolved oxygen in Budd Inlet, as discovered through recent studies by the Department of Ecology. In its early days, Capitol Lake was a place for swimming and boating, but now it is a public health hazard, overcome with invasive species, and "closed until further notice." Some people are nostalgic for the early days of the lake and what it once offered for recreation and beauty. They would like to see the lake healthy again. However, the lake cannot be managed back to health. The issues of invasive species, sediment management and poor water quality will not improve with the dam in place. Science has indicated that a much deeper Capitol Lake would still not meet water quality standards. Dredging alone does not provide an answer. Some argue the economic impact of restoring this estuary is harmful. While we do need to consider and plan for the increased sediment loads anticipated for the Port and marinas, we also have to look at the new economic benefits from the restoration economy. In addition to the priceless and freely given services of the ecosystem itself, we would create local job opportunities. Restoration funding from many local and national sources would stream into our community. It would create jobs for scientists, engineers, construction workers, restoration specialists and native plant cultivators. The salmon, an economic driver for the Puget Sound area, would benefit with 260-acres of critical estuarine habitat. Environmental educators would bring students of all ages to learn how to bring places back to life. It would recreate places for recreation, building a market for equipment sale and rental. Restoration also creates a draw for tourism, as proven by the Nisqually Delta and the Elwha River. People are eager to witness and participate in the healing of broken places. Dani Madrone is the Volunteer Coordinator for the Deschutes Estuary Restoration Team (DERT). DERT is working to restore the urban estuary by reconnecting the river to the South Puget Sound and the Salish Sea. Visit our website at www.deschutestuary.com for more information and find out about volunteer opportunities.

Back to Home page. |

During the recent shutdown of the federal government, the Nisqually estuary was closed. The heavy metal gates were shut and locked, public access was denied. Restored and preserved as a National Wildlife Refuge, Nisqually was one of the many federal programs across the country that was deemed "non-essential."

During the recent shutdown of the federal government, the Nisqually estuary was closed. The heavy metal gates were shut and locked, public access was denied. Restored and preserved as a National Wildlife Refuge, Nisqually was one of the many federal programs across the country that was deemed "non-essential."